No, this is not an article about ninja warriors but about how Chinese policies on waste have impacted recycling and waste management in the UK (and elsewhere).

A bit of history...

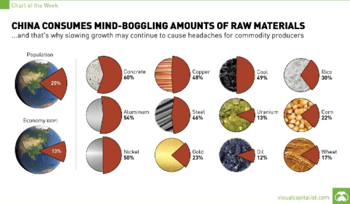

As Chinese industries producing mass market products have grown so has their appetite for raw materials. China has become the world’s largest consumer of raw materials since its industrialisation began 30 years ago. Among its imports are also secondary raw materials, what we know as recycled materials. These were often cheaper to buy and given low environmental standards in China, cheaper to convert into new products which China then exported back to where the waste had come from.

As Chinese industries producing mass market products have grown so has their appetite for raw materials. China has become the world’s largest consumer of raw materials since its industrialisation began 30 years ago. Among its imports are also secondary raw materials, what we know as recycled materials. These were often cheaper to buy and given low environmental standards in China, cheaper to convert into new products which China then exported back to where the waste had come from.

A cycle emerged.

We exported our recyclates to China who converted them back into products it sold back to us. The reverse logistics (empty containers from Europe returning to China) at very low cost, made all this possible. Our recycling systems (you putting your paper, plastics, cans and bottles into bins outside your front door) fed Chinese industry. All this has gone on for about 15 years. Recyclates from across Europe, the USA, even Japan and Australia, were sent to China. While you thought you were recycling to drive domestic recycling and industrial re-use, actually about half of those materials were heading east.

As the EU and other countries imposed ever higher recycling targets, the markets for those products were mostly not at home, but in south-east Asia, especially China. At its peak, China imported around 9 million tonnes of plastic waste, and the UK alone exported 3 million tonnes of cardboard waste to China in 2017.

As the EU and other countries imposed ever higher recycling targets, the markets for those products were mostly not at home, but in south-east Asia, especially China. At its peak, China imported around 9 million tonnes of plastic waste, and the UK alone exported 3 million tonnes of cardboard waste to China in 2017.

See the report issued by the International Solid Waste Association in 2014 on plastic exports if you want a lot of detail on this:

https://www.iswa.org/fileadmin/galleries/Task_Forces/TFGWM_Report_GRM_Plastic_China_LR.pdf

Then something changed.

China committed to the Paris Agreement (under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) in December 2015 and it is taking its commitment seriously. Among the ways in which China can reduce its greenhouse gas emissions is better managing its waste. This means more recycling and less dumping. Open dumps burning near cities contribute to poor air quality too, whilst low quality treatment of many waste streams meant that part of the imported wastes ended up in the open environment.

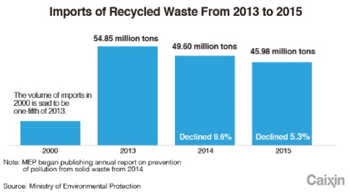

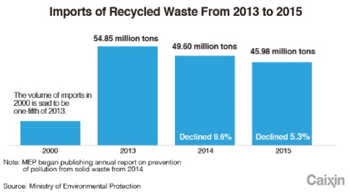

Conversely, as China’s consumer demand has grown, it has also created its own stock of waste materials that can be recycled – the Chinese throw away plastic bottles and newspapers too. Even before 2015, waste imports were slowly declining as local resources were increasingly available. The authorities therefore came to the conclusion that by banning waste imports they could catch many pigeons with one stone – reduce pollution back home, drive up demand for domestic recyclates, reduce the cost of imports, help meet their climate change treaty commitments.

Conversely, as China’s consumer demand has grown, it has also created its own stock of waste materials that can be recycled – the Chinese throw away plastic bottles and newspapers too. Even before 2015, waste imports were slowly declining as local resources were increasingly available. The authorities therefore came to the conclusion that by banning waste imports they could catch many pigeons with one stone – reduce pollution back home, drive up demand for domestic recyclates, reduce the cost of imports, help meet their climate change treaty commitments.

In January 2018, China announced a ban on importing recycled materials with more than 0.5% impurities for as many as 16 different waste types – which will extend to 32 waste types by end 2018.

And all hell has broken loose.

Just google “China waste ban” and you will get headlines that show how the recycling industry is in a mess over this. The US has formally asked China to rescind the ban which is disgracefully hypocritical, as the US has withdrawn from the Paris agreement; “mountains” of waste are piling up all over the place; exports to other east Asian nations are increasing to take up some of the capacity; landfills and incinerators are working flat out to dispose of lots of materials no one seems to want. And prices of waste paper, plastics and metals (already declining due to oversupply) have fallen dramatically.

Just google “China waste ban” and you will get headlines that show how the recycling industry is in a mess over this. The US has formally asked China to rescind the ban which is disgracefully hypocritical, as the US has withdrawn from the Paris agreement; “mountains” of waste are piling up all over the place; exports to other east Asian nations are increasing to take up some of the capacity; landfills and incinerators are working flat out to dispose of lots of materials no one seems to want. And prices of waste paper, plastics and metals (already declining due to oversupply) have fallen dramatically.

Meanwhile the EU has recently passed new laws requiring us to recycle 65% of our waste by 2035, about twice the current levels (when taking into account the way in which we calculate this will change too). Where will it all go?

Why all this recycling if there is no market for it all?

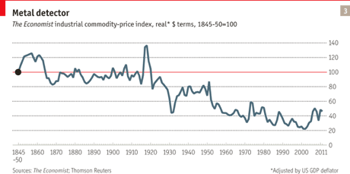

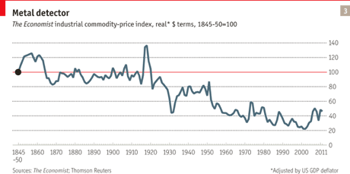

Truth is, China has exposed the truth about our waste management. We feel virtuous about recycling our waste but in reality we don’t have much use for a lot of it. As long-term raw material prices in real terms continue to fall, recycled materials become less valuable – which is why millions of tonnes of plastics end up in the oceans every year.

Truth is, China has exposed the truth about our waste management. We feel virtuous about recycling our waste but in reality we don’t have much use for a lot of it. As long-term raw material prices in real terms continue to fall, recycled materials become less valuable – which is why millions of tonnes of plastics end up in the oceans every year.

Clearly producing new materials is still much cheaper than recycling them (not always, but usually); unless very low standard recycling can find use for them (as it was in China and is now in Vietnam, Philippines, Cambodia and so on) or high quality and high purity products can effectively replace virgin materials (for example, aluminium cans) – then recycling works. Usually however, recyclates are contaminated because our collection and treatment schemes do not separate waste very well and this reduces the technical ability to recycle them.

What to do?

Some short answers, because it's complicated, I will try to simplify.

Prevention: Let’s start using less packaging, less materials and design out waste. It is top of the waste hierarchy but damned hard to do. You can make a difference by choosing products at the shops that have least packaging or compostable packaging that can be home or industrially composted and elect to go “plastics free” as the campaign group, A Plastic Planet advocates.

Prevention: Let’s start using less packaging, less materials and design out waste. It is top of the waste hierarchy but damned hard to do. You can make a difference by choosing products at the shops that have least packaging or compostable packaging that can be home or industrially composted and elect to go “plastics free” as the campaign group, A Plastic Planet advocates.

We need to use less, simply.

Recycle: By this I mean we need to ensure that the materials we want to recycle actually can be. So we need to make materials easier to recycle and to ensure we legislate so that we use recycled materials in new products. Newspapers for example are around 40% recycled content. The Co-Op is introducing a water bottle with recycled content, that won’t look as clear as a virgin product, but ensures plastics are re-used. Ecover the detergent company is using recycled plastic in its bottles; Coca-Cola have committed to tough targets on using recycled plastics in their bottles.

We need to actually recycle, simply.

Invest domestically: The new scenario of having large volumes of materials collected for recycling that no longer have export markets to China presents an enormous business opportunity for the developed countries to transform these into products people want to buy, currently imported from China. Of course we don’t have the low labour costs that China has but were we to use those materials to make new products, we wouldn’t have the transport/logistics costs of exporting waste to China and reimporting their products; and we could use latest technologies to ensure low-cost mechanised manufacturing. We need to look at which markets, products and materials we currently import that we could competitively make here.

Invest domestically: The new scenario of having large volumes of materials collected for recycling that no longer have export markets to China presents an enormous business opportunity for the developed countries to transform these into products people want to buy, currently imported from China. Of course we don’t have the low labour costs that China has but were we to use those materials to make new products, we wouldn’t have the transport/logistics costs of exporting waste to China and reimporting their products; and we could use latest technologies to ensure low-cost mechanised manufacturing. We need to look at which markets, products and materials we currently import that we could competitively make here.

We need to make more of own our resources, simply.

Subsidise and tax: As we have seen, virgin raw materials still cost less than most recyclates. This is because the externalities of mining, logging, catalysing from oil and their associated CO2 emissions and environmental damage are not priced in. It is crazy that it costs less to dig gold out of the ground than recovering it from used electronic goods where the concentration is many times higher. Which is why mountains of used phones, computers and TVs are everywhere. By pricing in these externalities through environmental taxes (like landfill taxes or Extended Producer Responsibility [EPR] schemes and carbon taxes) and subsidising the cost of recovering and recycling these materials, we can recycle more. The UK pays very little into these programmes, maybe a fifth or sixth of what equivalent programmes cost in Europe, explaining why effective recycling of plastic waste in the UK is only 9% of what is thrown away. At a global level we give four times more subsidies to oil producers than to renewable energy producers. Yes, you read that correctly. Which explains some of the mess we have around not recycling materials and using too much oil and coal.

We need to make polluters pay, simply.

Conversely, as China’s consumer demand has grown, it has also created its own stock of waste materials that can be recycled

Conversely, as China’s consumer demand has grown, it has also created its own stock of waste materials that can be recycled

Truth is, China has exposed the truth about our waste management. We feel virtuous about recycling our waste but in reality we don’t have much use for a lot of it. As long-term raw material prices in real terms continue to fall, recycled materials become less valuable

Truth is, China has exposed the truth about our waste management. We feel virtuous about recycling our waste but in reality we don’t have much use for a lot of it. As long-term raw material prices in real terms continue to fall, recycled materials become less valuable  Prevention: Let’s start using less packaging, less materials and design out waste. It is top of the waste hierarchy but damned hard to do. You can make a difference by choosing products at the shops that have least packaging or compostable packaging that can be home or industrially composted and elect to go “plastics free” as the campaign group, A Plastic Planet advocates.

Prevention: Let’s start using less packaging, less materials and design out waste. It is top of the waste hierarchy but damned hard to do. You can make a difference by choosing products at the shops that have least packaging or compostable packaging that can be home or industrially composted and elect to go “plastics free” as the campaign group, A Plastic Planet advocates.